By guest writer Leanne Lemaich*

Ramps or wild leeks are one of the spring season’s first green edible offerings. These tasty root vegetables are a staple of Indigenous cultures in North America, who traditionally harvested ramps as

both medicine and the first greens eaten after a long cold winter.

Ramps are slow growing with limited seed production, and unfortunately, populations in Ontario are decreasing. There are sustainable and responsible harvesting techniques for foragers to ensure ramp populations for generations to come, so they too can experience this culinary delight.

The two Ontario ramp variants

- Allium tricoccum var tricoccum: A large burgundy-stemmed variety with large green leaves that are 5 to 9 cm wide and produce umbels with 30-50 flowers.

- Allium tricoccum var burdickii: A less common white- and green-stemmed variety with smaller green leaves that are 2-4 cm wide and produce umbels with 12-18 flowers

Both variants can be recognised by their distinct scent of onion and garlic. The leaves die off in June and flowering begins mid-summer. They produce umbels with multiple small flowers that are cream or white. Pollinated flowers produce a tiny green fruit followed by small black seeds. Both the bulbs and leaves are edible and sought after for their unique flavour and nutritional benefits.

Why are populations decreasing?

Ramp populations in Ontario are declining for several reasons:

- They take at least 7 years to reach maturity and begin reproduction.

- Seeds can take up to 2 years to germinate.

- Destruction and development of woodlands and habitat is ongoing.

- Ramps are being overharvested.

How to harvest responsibly and sustainably

Slow-growing ramps are a unique and highly prized forgeable, susceptible to habitat loss and overharvesting. There are two different foraging strategies, one for privately owned land where there is limited foraging and harvesting and one for Crown/public land where many foragers may be harvesting a given plot or area.

Foraging on privately owned land

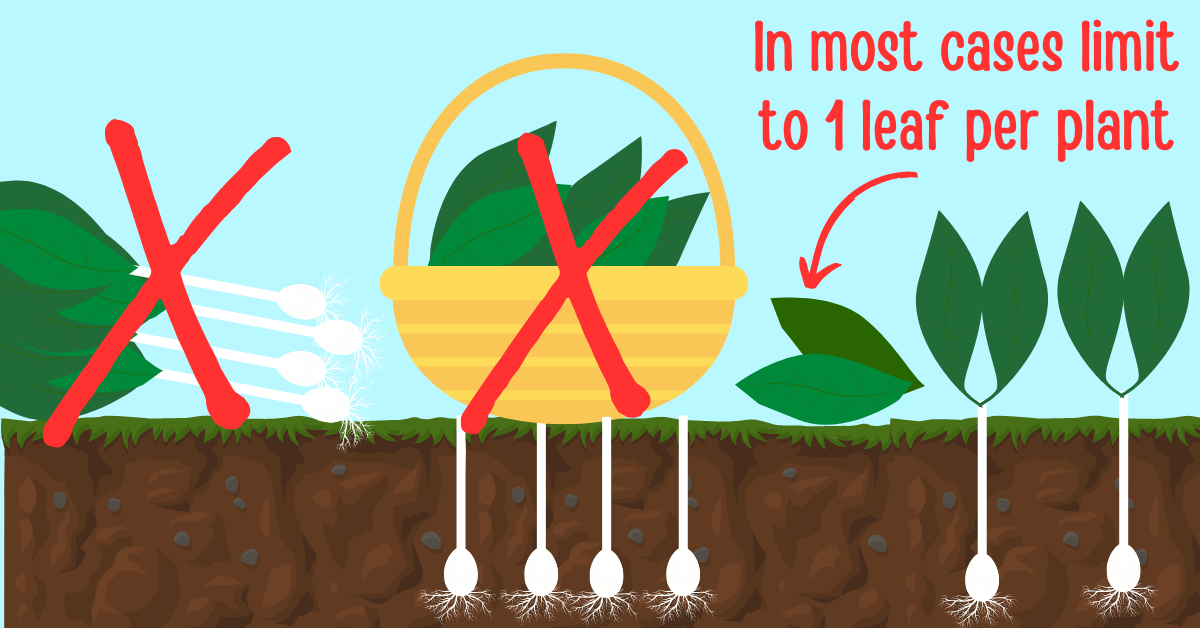

Make sure you have permission to be foraging on privately owned land. Since on private land ramp harvest is limited and populations can be monitored, it is recommended that foragers:

- Limit general harvest to a single leaf from mature plants with 2+ leaves—wait until late in the season after plants have had the opportunity to photosynthesise and store energy.

- Harvest the bulb where bulb density >90 bulbs/square metre—in this case, thinning the plot can be beneficial to the remaining plants

- Limit bulb harvest from each plot to once every 10 years

- Do not harvest fully mature plants that have reached reproduction age

- Be mindful of the forest understory—use a small hand trowel to dig instead of a large shovel that damage plants and the surrounding ecosystem

- Never take more than you will use or eat

Foraging on Crown/public land

On Crown/public land, multiple foragers may be harvesting so it is recommended that foragers:

- Limit harvest to a single leaf from a mature plant with 2+ leaves—wait until late in the season once plants have had the opportunity to photosynthesise and store energy

- Never harvest bulbs as you cannot be certain you are the only forager harvesting from that area

- Never take more than you will use or eat.

- Do not forage in parks and conservation areas as it is illegal to do so in Ontario.

It can take years for wild leeks to recover from overharvesting. In Ontario wild leeks are not protected under the Ontario Species at Risk Act, but they are being constantly monitored in case their status requires reclassification. However, in other provinces like Quebec, where populations have substantially decreased, ramps are protected with harvest limits. It is your duty to know the rules and regulations regarding harvest in your area before heading out to forage. Failure to do so can lead to fines and limited future harvests.

How can you help?

Ways to help bolster the native ramp population in your region:

- Collect seed from mature plants and plant them in the area that same fall

- Carefully transplant small bunches of ramps from large densely populated patches to areas with similar soil types and conditions without a ramp population

- Do not buy ramps you cannot ensure have been responsibly or sustainably harvested from foragers

Ramps transplant well; however, transplanted ramps should not be harvested for a number of years until they’re well established with mature plants producing flowers and seeds.

Preparing to forage

Before heading out, be prepared:

- Have all the necessary equipment including a trowel, knife, bags and a basket

- Wear appropriate clothing and sturdy footwear

- Don’t forget something to drink and bring some bug spray

- Arm yourself with the knowledge to harvest sustainably and responsibly and know the regulations and laws in your area

While foraging…

- Take a moment to appreciate the amazing and beautiful ecosystem surrounding you

- Be thankful for and appreciative of your harvest

- Never take more than you need

Be safe and happy foraging!

If you have any foraging questions, email info@cleannorth.org, and we will ask Leanne to answer them.

*Raised in Sault Ste. Marie and Sudbury in the 1970s, Leanne later moved to southern Ontario where she attended the University of Western Ontario. She now lives in the Long Point area and works as a kayak guide and ecosystem educator.